PG Showcase: Mason Norton on Resistance in Upper Normandy, 1940-44

Whether you prefer to call it ‘The French Resistance’ or ‘resistance in France’, the subject of resistance during the Second World War in France poses an interesting paradox for the historian. Whereas most historians of the 20th century work with an abundance of written sources, the sources here tend to have been constructed after the war, whether they be oral or written, with the exception of a few resistance newspapers and police reports, both of which have to be taken with considerable pinches of salt. Yet this is a period that is both relatively recent, with a handful of remaining anciens résistants still remaining, whereby the landmarks are familiar, and which poses questions about the nature of engagement and existence, and the relationship between states, individuals, collectives and societies, that are as pertinent to our era as to the 1940s.

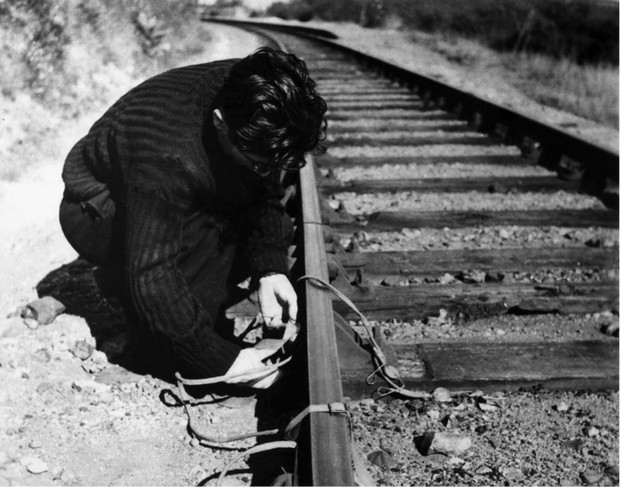

The image of resistance usually given is that of either a patriotic struggle or of Communist engagement, of attacks against occupiers or sabotages, or of far-fetched escape plans. It is, essentially, a ‘screen memory’ that has, in turn, been lionised, mythologised, belittled and parodied.

A resister shown sabotaging a railway line in Normandy (reconstruction, 1944)

The aim of my research is to try and cut through these images, whilst at the same time acknowledging the construction of these received ideas, and considering the questions about engagement and the interactions between people as individuals and society as a collective, taking into account factors such as capital (in the sense of the term used by Pierre Bourdieu), ideology, and gender. Typically, resistance in the region of Upper Normandy has not had a central role in the local narrative of the Second World War, yet it was active and as varied as in many other French regions. But whereas the organisation of the Resistance has been charted here, I am interested in the functioning of resistance as a behaviour by individual and collective agents, framed in the context of a struggle against both the Nazi occupation and the collaborationism of the Vichy regime and its supporters. How did resisters combat not just the military force of occupation, but also the hegemony and the coercive collaboration of Vichy? What were the links between the social composition of Upper Normandy at this time and roles played in resistance? What were the aims and practices of resisters? What were their visions of the past, present and future, and how did these impact upon their resistance action? How can we qualify and interpret their behaviour? This is to be done by focusing primarily upon the testimony of the resisters themselves, both written and oral, and applying an interpretation of these sources to arrive at an understanding of the nature of resistance as a form of engagement during the Occupation, applying what I see as essentially the aim of the historical method- l’administration des preuves afin qu’on puisse comprendre l’autre.

My argument is that resistance should be seen not through the prism of military history, but instead through the prism of resistance studies, and therefore as a political behaviour. By this I mean that it was not necessarily an adhesion to a political party or about wanting to seize and wield power, although these considerations were present. It was about the political in the sense of le politique rather than la politique, an engagement for a common good in the sense of polis or la cité; politics not as an exclusive domain uniquely concerned with the couloirs du pouvoir, but as an intersectionality of different cultural and societal factors. As an engagement with the society around themselves, resistance as a behaviour was inherently political by its very existence.

Mason Norton, Edge Hill University